David Joy‘s debut novel Where All the Light Tends to Go hit…

We Got Lucky: My Life with Tom Petty

I was seventeen when I first loved him.

Seventeen and a complete mess. I had recently “gone wild.” That’s what people in my church said. All my life I had been the perfect little Holiness boy, and I had only recently started to drink: Natural Light or Jim Beam. And I had taken up smoking Marlboro Reds, as anything else was too weak for the standards of my crowd. I also sneaked into local honkytonks that had names like The Maverick and The Mustang and The Spot. I got in with a fake ID I purchased from a boy in my class who worked at Kmart. He had access to a laminating machine in the gun department, where they made hunting licenses, I suppose. Sometimes I just waltzed right into the club, no questions asked. Things were different back then.

We danced as if our lives depended on it. Every part of us moved, twisted, shook. We danced to Bob Seger and Prince and Janet Jackson. We took shots of the whiskey and chased them with the beer. We threw our heads back in laughter. We smoked cigarettes and fancied that we looked like movie stars while doing so—Matt Dillon in The Outsiders, Kevin Bacon in Footloose.

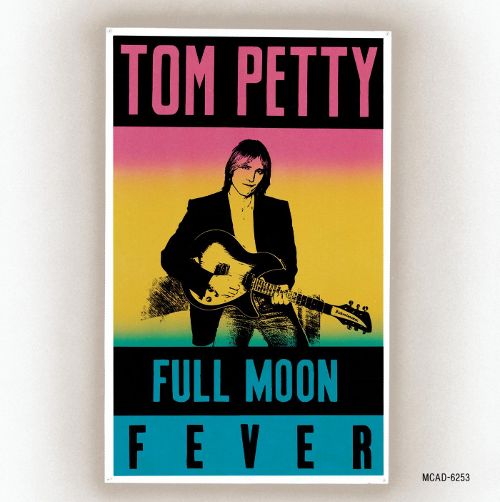

But the best part was when we sang together. We sat in a circle around those sticky, round tables burdened with cans, bottles, and plastic cups, and we were always loudest when Petty came on. We put our arms around each other’s necks and let loose at the tops of our lungs to “I Won’t Back Down” and “Yer So Bad” and “Free Fallin’.” We knew every word to every song on his Full Moon Fever album. We adored him. Everyone I knew did.

Tom Petty defined who I wanted to be at that moment. For a Southern man, there were many ways that I was “supposed to be”. But he was the kind of Southern man I wanted to be: cool, tough, and sensitive all at the same time. He didn’t have matinee idol looks but he did have magnetism—and he could play the hell out of that guitar. Plain enough to not be threatening but sexy enough to make us want to be like him. He sang about losers and somehow we believed he was one of them, just like us, even though we idolized him. Petty had no intentions to hurt anyone. He had only the best intentions: to drink and smoke and sing and dance and love each other. I loved him, yes. And somehow, he saved me.

From the time I was sixteen, I worked in a series of restaurants. When we closed in the evenings, my co-workers and I would often drive the few miles from Corbin, Kentucky, to Laurel Lake. We stripped down to our underwear at the Three Sisters, three huge boulders that towered above the water at perilous heights. We dared each other to climb higher until we were finally ready to jump one-by-one—twenty, thirty, forty feet down into the water. Then we drank and smoked, sitting back to watch the moon drift through the blue-black sky.

The boys I went swimming with were good ole country boys. They loved country music, especially Hank Williams, Jr. We all sang “Family Tradition” and “A Country Boy Can Survive” to that lake-drifting moon, trading verses as we treaded the midnight water. We joined together for rousing choruses of Merle Haggard or Mellencamp.

But nobody spoke to us the way Petty did. We sang Don’t want to live like a refugee and Baby I’m an insider, I been burned by the fire. We knew all the words to his songs.

I first remember hearing him when I was eight years old and he was singing “Don’t Do Me Like That.” My cousin Eleshia was speeding down the highway with the radio turned all the way up and all the windows down, her black hair flailing around her face. “Sing it with me, Little Man!” she called out.

When I was fourteen, my wild aunt, Sis, bought a copy of his album Southern Accents, and on hot summer evenings she’d put it on the record player and we’d sit on the porch listening to it through the opened windows. The title song was a source of pride for us. It summed up all our feelings about being from the South without an ounce of the things that frequently marred that identity. There was no racism, no machismo, no striking out at Otherness. There was only love for the place, an articulation of that inexplicable connection we Southerners have to a landscape, to a cadence, to a way of being. During his tour to promote the album, a Confederate flag was used onstage during one song, but Petty quickly realized his error and asked audiences to not bring the offensive flag to his concerts. Later, when it showed up in the interior booklet of a live album, he asked the record company to remove it. He showed us that we could embrace our Southerness without the bragadaccio, without the racism, without the bullshit.*

Full Moon Fever cemented the deal for me. That record was the soundtrack for my senior year of high school and far beyond. Yes, my friends and I partied to it cranked all the way up. But I also listened to it when I was alone, trying to understand who I was. It took me a long time to figure that out. All the while, I listened to that album, especially savoring its quieter moments.

Then, in 1994, my favorite album of all time was released. Petty’s Wildflowers is a masterpiece. The first of his three albums produced by Rick Rubin, it is sonically rich. The Heartbreakers—not credited on the cover, but all there, jamming away—are on fire throughout, and the songwriting is revealing, moving, and, above all, resonant. Just about anyone could relate to “You Don’t Know It How Feels,” and it was impossible to hear it without singing along, without nodding your head, without tapping your foot. There was “You Wreck Me,” which was impossible to not dance to. Most of all, there was the title track, one of his best songs because it is so simultaneously simple and profound. “Wildflowers” is Petty telling anyone who is listening that they matter, that they’re beautiful, without ever once falling into sentimentality. Every song on the album is a gem, each one a part of a whole I have listened to from beginning to end over and over again, often in the most difficult phases of my life.

When Wildflowers came out, I was twenty-four, the father of a new baby girl, and then, suddenly, a married man. I was crazy over my daughter and felt completely transformed by her existence. All at once I didn’t care about partying any more. I didn’t care if I ever went out drinking and dancing. I just wanted to be with her. As soon as she was born, I knew that my whole reason for being was to be her father. For the first time in my life I felt like I knew who I was.

Every night I sat up late with her. Like me she was a night owl, even as a baby. Whatever I was reading, I read it aloud to her. She sat content in the crook of my arm, her eyes following along the lines of novels like Jude the Obscure, Beloved, or Dolores Clairborne. And I played music for her. Gillian Welch, Whiskeytown, Mellencamp, Lucinda Williams. But always, always Petty. When her eyes became heavy, I rocked her back and forth and sang So close your eyes we’re alright for now or You belong among the wildflowers. Those two songs always did the trick. Twenty years later, those are two of her favorite songs and she has remarkable taste in music. I’m an evangelist for osmosis because of it.

When she was a few months old, my cousin bought us tickets to see Petty in the nearest city, about an hour away. I didn’t want to leave my daughter for the night, but I also knew I’d always regret it if I didn’t see Petty live in concert—and some part of me knew that she’d grow up to be the kind of woman who would be glad I’d gone to see him. My whole family thought it was wrong of me to leave the baby and go to a concert. Actually, they thought it was wrong to go to a concert, period. My new role as a father gave my church-going family hope that I might eventually follow their original dream for me to become a preacher. But that wasn’t in the cards. Instead, I became a writer.

I went to that concert, and my cousins and I danced and sang all night. We saw him at Rupp Arena, in Lexington, Kentucky, with more than 23,000 other people who had been carried through their lives by his music, who knew all the words, who seemed to sing each one of them on every single song. We embraced strangers and threw our heads back and sang. This was a kind of church, too, I thought. A room full of love in a way I’d never experienced before.

In the years since I’ve bought every single album Tom Petty has released. I’ve kept singing along with him. I’ve watched my daughter and her younger sister, who came along almost three years later, both grow up. Perhaps one of the proudest moments of my life is when my eldest got into her car one day and left our driveway with the windows down, “American Girl” playing as loud as it would go.

I don’t quite know how we properly articulate our love for someone we have never even met, especially a musician who has touched our lives. But that’s the thing about an artist like Tom Petty: we needed him to put those profound and important things into perspective for us in a four-minute song, in a perfect riff, in that way of singing he had that was equal parts sorrow and joy. What I’ve been trying to say, in the end, was much better articulated by him years ago: “Music is probably the only real magic I have encountered in my life. There’s not some trick involved with it. It’s pure and it’s real. And it moves and it heals and it communicates and does all these incredible things.”

For so many of us, that’s what he did. That’s what he meant.

__________________________________________

* A full essay by Petty on this subject can be found here.

Love Tom Petty. Love this. Another great piece, Silas.

Great piece, Silas. You’ve captured his ability to make us sing his anthems at the top of our lungs or linger in the tenderness of his words alone.

Your article on Tim Petty pretty much sums up my feel8ngs entirely. Well written.

Oh! marvelous post. Thank you, Krista.

just loved it. ‘ve got another one

What a beautiful article and great tribute to an awesome artist. I grew up listening to Tom Petty as well. I could picture every moment in your story as if I were there. I’m glad you never stifled your writing talent to follow your family’s dreams for you!

What a great article on Petty. And just plain music back in the days, I was and still am in love with the 70s. Life was much simpler back then, didn’t see or feel the hate that’s going around these days, Music was my escape back then. As it still is to this day, when I’m having a bad day weather it be due to depression, my battle with Multiple Sclerosis, all I have to do is put on some music from back in the 70s. I sit back and feel myself back in those days, some Beatles, Zeppelin, Sabbath, Creadence, The Who, Dam I could go on and on. Music is my Sanity. My Escape from the ugly Ness that has become such a heartache these days. I pray things change before it’s to late,

Tom. Boston

Good post.I liked it very much

ravi

This was really well written. Thanks for writing it.

Jessika

Good stuff😍😍

I’m 34 and I consider Full Moon Fever to be the soundtrack to my life. I was devastated when he passed away in a way. It was like a member of my family had died.

I think when the music is really, really good it can have that affect on you.

Great post!

So disappointed when reading WordPress’s “top blogs” but by chance happened to find you and this piece. And my hope to find a human being with a real life and the ability to write it to us was restored.

So now I’m posting this comment with Tom Petty coming from the box beneath the table, one YouTube video after another. I think I will “come around here” some more.

And I’ll look for a book or two from a new southern brother….

This was so touching. Growing up in the south I can relate to this in so many ways. My brother and I grew up listening to Tom Petty. He is one of our favorites thanks to my parents. I had tickets to go see him in New Orleans this past summer. A squall came through and canceled all the shows that day. He ended up performing anyway but it was too late for us to get there. I was devastated but his music will live on forever. Thank you for this read!

I’m so glad I stumbled across WordPress again after a lengthy hiatus. This piece was wonderful and completely articulated my youth and the huge impact Petty, and music in general, plays in our lives. Thanks for writing this.

I was touched by this piece and I still feel a little bit of loss every day. And I know that is strange for someone that I never met. The last full paragraph resonated with me in a very unique way because I felt similar emotions when he passed away too. https://flatcircleblog.com/2017/10/04/thoughts-on-tom-petty/

I feel like I was right there beside you singing those lyrics and taking in life and loving youth and love itself.